Ngwao no. 1: Conserving Trauma

Apartheid has left behind a landscape marked by violence, inequality, and suffering. The conservation of sites associated with this kind of historical trauma is a profoundly complex and ethically sensitive task. However, it is necessary for a healing country such as South Africa. This essay explores the conservation and adaptive reuse of the Women's Jail at Constitutional Hill in Johannesburg. This former prison complex held thousands of women, many of them political activists, under harsh and unjust conditions. Today, the site is a museum and civic space dedicated to memory, justice, and education.

Photo of Fatima Meer attending an exhibition at the Women's Jail. Kate Otten Architects.

Drawing on the frameworks of dark tourism (Lennon & Foley 200), trauma heritage (Tumarkin 2005), difficult heritage (Macdonald 2009), and traumascapes (Tumarkin 2019), this essay considers how conservation practice at the Women's Jail engages with histories of pain and survival while navigating the tension between remembrance and commodification. These concepts provide insight into how certain places, particularly those associated with suffering, acquire symbolic weight and attract public interest, becoming arenas for national reflection, moral confrontation, or even contested storytelling .

The essay also engages with key conservation frameworks such as the National Heritage Resources Act and ICOMOS's post-trauma recovery guidelines (ICOMOS 2017). These documents will help assess how ideas of authenticity and significance were understood and applied in the architectural and interpretive interventions. The role of social value in heritage practice is also highlighted, drawing from Jones (2017), who notes the tensions in defining what matters and to whom when dealing with contested pasts .

In examining the Women's Jail, the essay argues that while the conservation process reflects a strong commitment to retaining historical integrity and advancing restorative justice, it also reveals unresolved tensions. These include the risks of over-sanitising or aestheticising trauma, the commodification of memory, and the ethical complexity of inviting visitors to witness suffering in curated forms. By considering how memory, space, and affect are negotiated at Constitutional Hill, the essay reflects on the possibilities and limitations of trauma-informed conservation in a society still grappling with the legacy of structural violence and inequality.

Andrea. The entrance to the isolation block in number four prison. The original materiality of the entrance has been conserved for the most part. Photograph (2024). Happy Days Travel.

The Old Fort was built in 1893 under the direction of President Paul Kruger of the Boer Republic of Transvaal . Knows as the Johannesburg Jail, it was repurposed in 1896 into the city's first military Fort. During the South African War, the British took over the Fort and, by 1904, resumed its role as a prison . This would be the year the "native' prisons number four and five were built, and the prison was where the most influential freedom fighters, Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, and others, were detained . The Women's Jail was built in 1910 to hold women of all races .

For much of the 20th century, it served as the detention centre that bore witness to the incarceration and suffering of countless women, including political activists, ordinary citizens, and non-white women targeted by the apartheid state. Black, Coloured, Indian and White women were detained, with Black women forming the majority of detainees faced overcrowded cells, poor sanitation, and constant surveillance compared to the other detainees. By contrast, white inmates received preferential treatment, including more spacious quarters and regular visits from clergy and family. According to Clair Ennis, the prison functioned as a "microcosm of apartheid society", enforcing rigid racial hierarchies even within the oppressive walls .

The prison was a space where state violence was enacted on women's bodies and identities. Many detainees were arrested during major protest movements, including the 1956 Women's March and the 1976 uprising. Prominent anti-apartheid figures such as Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, Barbara Hogan, Fatima Meer and Albertina Sisulu were imprisoned here; their experiences emblematic of the broader state-sponsored oppression faced by women resisting apartheid . However, beyond the well-known political detainees, the prison also confined thousands of women arrested for petty offences under the apartheid draconian pass laws, which controlled Black movement and labour, many of whose stories remain largely undocumented in mainstream historical narratives . Cecil Palmer, who was detained in 1976 while pregnant, recalled the fear she endured under the threat of violence from the security police . Lillian Keagile, another former inmate, stated: "The memories are so vivid… how we used to get beaten and humiliated. I still have bad dreams.

Despite the oppressive environment, many incarcerated women demonstrated resilience and solidarity. Fatima Meer, detained without trial in 1976, created clandestine artworks depicting daily prison life, offering a glimpse into the experiences of female prisoners . Barba Hogan's letters from prison further reveal the emotional toll of incarceration and the strength drawn from familial support.

Sunday Times. Fatima Meer, anti-apartheid struggle stalwart and first president of the South African Black Women's Federation. She was also a lecturer in Sociology at Natal University, Durban. 22 July 1970. Photograph. Gallo Images

These lived experiences contribute to what Maria Tumarkin refers to as traumascapes; "physical sites of violence and loss are much more than mere backdrops to the traumatic events and that they take place in their soil" . From the gruesome events retold at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, where women spoke on their experiences, describing horrific examples of sexual violence and torture in the jails against women and girls as young as fourteen . To the ordinary life in prison, where women braided one another's hair, played cards, and read bits of newspaper together . As Turmarkin puts it, traumascapes are "haunted and haunting places, where visible and invisible, past and present, physical and metaphysical experiences come to coexist and share a common space. These are places that get to us, that affect us at the very core, that make us feel everything from awe to unease, from fear to epiphany, from a burst involuntary memory to a sense of deep, all-powerful transformation" . The Women's Jail did not merely record trauma; it actively shaped how trauma is remembered, felt and performed in the present.

Additionally, the Jail has become a robust case of what Sharon Macdonal calls difficult heritage; "a past that is recognised as meaningful in the present but that is also contested and awkward for public reconciliation with a positive, self-affirming contemporary identity" . In this sense, the Women's Jail presents a record of institutionalised injustice and a space where South African society negotiates competing understanding of gender, race and resistance.

The Jail officially closed in 1983 and was later reimagined as part of the Constitution Hill precinct . Today, it stands as a site of both commemoration and contestation, and its transformation offers a poignant case of how the material remains of trauma are reworked into narratives of justice, democracy and resilience.

To understand the conservation of the Women's Jail, it is important to explore beyond the technical work of preserving the historic structure. This site is not just an architectural object but a place marked by deep social and emotional scars. Its conservation raises questions about how South Africa remembers pain, how we represent that pain to the public, and how we create spaces of reflection, healing, or confrontation. I draw on four interrelated theoretical frameworks to explore these issues: dark tourism, difficult heritage, traumascapes and trauma-informed heritage practice. Each concept originating from different fields forms a valuable lens for analysing how the Women's Jail has been transformed and what that transformation means in post-apartheid South Africa.

The concept of dark tourism, as described by John Lennon, refers to the fascination people "appear to have with our morality and the fate of others" . This refers to people visiting sites associated with death, suffering, and historical trauma . These sites often draw visitors who are seeking emotional or educational experiences, yet they also run the risk of commodifying pain. In the case of the Women's Jail, its role as a museum and public heritage space means that it now functions as a destination for visitors, many of whom may not have a personal connection to its past. This raises questions about the genuine engagement with the site's history or the risk of turning trauma into spectacle. Dark tourism, therefore, draws attention to how public interaction with sites of suffering can be meaningful or superficial, respectful or exploitative.

Andrea. City Sightseeing bus at Constitutional Hill. Photograph (2024). Happy Days travel

Closely connected to this is the idea of difficult heritage, as defined by Macdonald (2009). Difficult heritage refers to aspects of the past that are traumatic, contested, or morally troubling, legacies that societies struggle to accept or commemorate . The Women's Jail qualifies as a difficult heritage site because it forces South Africans to confront the racial and gendered violences of the apartheid state. Macdonald argues that the value of such sites lies "in how heritage is assembled both discursively and materially, the various players involved, and what they may experience as awkward and problematic, and the ways in which they negotiate this" While dark tourism focuses on visitors and the experience of witnessing, difficult heritage shifts the lens towards the old narratives, the silences that remain, and the power structures that shape interpretation.

Maria Tumarkin's concept of traumascapes provides another lens through which to look at the Women's Jail. Traumascapes are not simply historical locations; they are landscapes where trauma is felt in the atmosphere, architecture carries emotional residue, and memory becomes embodied . In this view, the Women's Jail is not just a preserved building but a site where pain is embedded in the walls, passages, and cells . Tumarkin reminds us that traumascapes are dynamic; the ongoing presence of memory shapes them, the people who visit them, and the narratives constructed around them. The conservation of Women's Jail involves more than just technical skill. It requires sensitivity to affect, emotion, and memory.

Bringing these ideas together is the emerging framework of trauma-informed heritage practice. Adapted from trauma-informed care models psychology and social work, this approach emphasises safety, trust, collaboration and empowerment . Applied to the Women's Jail, this raises important questions about the extent to which former prisoners were meaningfully involved in the interpretation process and whether the site actively supports healing or simply preserves trauma.

Together, these four frameworks form the analytical foundation of this essay. Dark tourism helps me think about how visitors engage with the site. Difficult heritage examines how contested histories are presented. Traumascapes highlight the emotional and atmospheric qualities, and trauma informed heritage sets an ethical standard for how conservation should be carried out. These concepts are not isolated; they are deeply connected. They help reveal the tensions between memory and marketing, healing and harm, authenticity and narrative control. They allow me to ask whether the site has been preserved and transformed into a space that respects the weight of its past while serving the present.

Kate Otten Architects. New offices in the existing courtyard of the Women's Jail. The Light weight material constrasts the existing heavy read brick. Photograph (n.d.) Kate Otten Architects

The Women's Jail conservation was undertaken in the early 2000s as part of the broader development of the Old Fort prison and the establishment of the Constitutional Court Precinct. The objective was to preserve the historical structures and repurpose them into spaces that engage the public, promote constitutional values, and support democratic dialogue . The Women's Jail was earmarked for conservation and adaptive reuse, retaining its identity as a site of incarceration while transforming it into a museum and civic resource. The architectural and curatorial strategies in this process reveal strengths and tensions in managing the site's trauma and historical significance .

Architecturally, the conservation was led by South African female architect Kate Otten, who adopted a sensitive approach aimed at preserving the original spatial experience of the prison while making the site accessible and meaningful to contemporary visitors. The intervention involved repairing the structure, stabilising key historical features, and integrating new exhibition infrastructure without damaging the existing structure. Original prison elements were kept, such as barred windows, concrete floors, metal doors, and narrow passages. These elements play a crucial role in what Tumarkin refers to as the "affective density" of traumascapes, where the physical environment acts as a memory container .

The conservation of the Women's Jail was a deeply rooted pursuit of authenticity, but this authenticity is not singular; it operates on two interdependent levels. The first is material authenticity, which concerns the preservation of the physical fabric of the site. That is, the building objects on the site and their material value are important to the architectural history of Johannesburg and the country. The second is experiential authenticity, which refers to the intangible, embodied memories and lived experiences of the women imprisoned here. Together, these dimensions inform a holistic understanding of authenticity that moves beyond mere technical restoration.

Kate Otten Architects. Ground Floor Plan Showing the existing and new programming. Drawing (n.d.). Kate Otten Architects.

The National Heritage Resource Act (NHRA) of 1999 provides for this by mandating the conservation of heritage resources, safeguarding both their tangible and intangible qualities. Section 3 of the NHRA defines heritage significance as encompassing not only architectural and historical value but also association with "a particular community or cultural group for social, cultural or spiritual reasons" and "its strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group or organisation of importance in the history of South Africa" This dual definition would have formed a crucial legal foundation for the integrated conservation of the Women's Jail. The conservation project also aligns with the values outlined in the ICOMOS (2017) report on post-trauma recovery, which emphasises inclusion, dignity, and restorative practices to foster sustainable development and community well-being.

The understanding of authenticity adopted here resonates with the views of Webber Ndoro, who argues that in African contexts, authenticity cannot be confined to the fine material object alone but must reflect the "meaning and values communities attach to a place" Ndoro stresses that the conservation of heritage sites in postcolonial societies must acknowledge the voices and experiences of those historically marginalised by dominant heritage discourses. Centring the memories, trauma, and resilience of Black women who endured incarceration under apartheid becomes the case of Women's Jail. Echoing Ennis on the site's power to "help us remember these women and understand just how much they gave for the freedom of South Africa".

Herb Stovel builds on this argument by emphasising that authenticity is not a fixed attribute embedded in material objects, but a culturally and contextually situated judgement about what is meaningful and why. The Women's Jail attempts to meet this challenge by maintaining the prison's original spatial atmosphere while incorporating oral histories, personal artefacts, letters, and artwork into the experience. This spatial strategy also supports what Macdonald describes as the "critical museology" of difficult heritage, where visitors are encouraged to feel discomfort and reflect on injustice rather than passively consuming history.

The revised curatorial transformation developed stories of women detained at the prison, drawing on oral histories, photographs, court documents, letters, and artworks created in or about incarceration. According to Jumarali et al. (2021), such survivor-centred approaches are essential in trauma-informed heritage practices, as they centre power on the community in research and collaborative decision-making, emphasising the importance of listening, creating safe spaces and holding space for individuals to articulate trauma and bear witness .

Kate Otten Architects. Elevation and Section showing the new modern addition that contrasts the old. It exists just along side the old. Perhaps that is how we have dealt with the violent history. Drawing (n.d.). Kate Otten Architects.

However, some tensions remain. The dual function of the Women's Jail, as both a museum of suffering and an active space housing offices and public programs, raises questions about the boundaries between remembrance and reuse. While adaptive reuse is often necessary for sustainability, I question how the architects and curatorial team mitigate against the risks, softening the emotional intensity of the site. Introducing modern amenities, "polished finishes" in certain areas, and administrative functions may undermine the atmosphere of solemnity that the original architecture conveys. Macdonald (2009) reminds us that difficult heritage is most powerful when its discomfort is not entirely resolved, allowing visitors to grapple with its complexities and contradictions rather than presenting a neatly packaged narrative.

Overall, the Women's Jail's conservation and adaptation reflects a thoughtful and ethical response to the challenge of preserving a site of trauma. The architectural approach respects material authenticity and spatial memory, while the curatorial work attempts to centre survivor narratives. However, the site reveals the fragility of balancing conservation with public use and the need for continued, meaningful engagement with those most affected by the histories it holds.

Kamiso Wessie. A Guided tour of Number Four. Photograph (2023) inyourpocket.

The conservation and adaptation of the Women's Jail at Constitutional represents a meaningful attempt to preserve one of South Africa's most painful and politically charged heritage sites. Through sensitive architectural interventions and the partial integration of survivour narratives into curatorial practices, the project engages with the site's material and emotional dimensions. Retaining the prison's austere spatial character while layering it with stories of resistance reflects a commitment to conservation as a socially responsive and ethically aware practice.

Using the interconnected frameworks of dark tourism. Difficult heritage, traumascapes, and trauma-informed heritage, I attempted to show that the Women's Jail is not just a place of memory but also a site of affect, ethics and public responsibility. As a traumascape, it holds the emotional residue of incarceration, with architecture acting as an archive of suffering. As a site of difficult heritage, it forces society to confront uncomfortable truths about apartheid's gendered violence. As a location of dark tourism, it invites public witnessing but also risks commodifying the pain of others. Finally, through a trauma-informed lens, the site raises essential questions about participation, narrative control, and the long-term inclusion of those whose lives it represents.

Ultimately, the conservation of the Women's Jail is not perfect. It demonstrates how conservation can support healing and public dialogue by honouring affective space and the voices of survivors. However, it also reminds us that difficult heritage is never fully resolved. It must be actively maintained through continuous ethical reflection, community engagement, and willingness to sit with discomfort. In this way, Women's Jail becomes not just a space of history but, like its struggling heroines, a living site of moral reckoning. Reminding us that the built environment can serve as a witness and teacher in the ongoing struggle for justice.

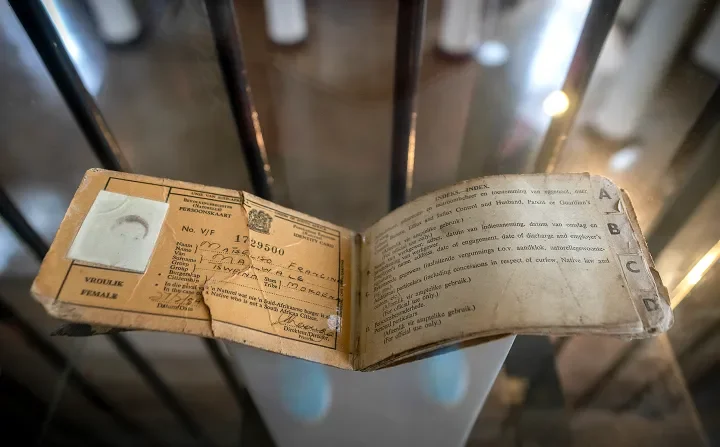

Shiraaz Mohamed. An exhibit of a passbook is on permanent display at the women's Jail. Pass laws helped the government to control where black people could live and work in South Africa. Photograph (2022) DailyMaverick

Bibliography

Appasamy, Youlendree. 2017. Fatima Meer's Artwork: A Miraculous Testament Against Forgetting. September 7. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.kajalmag.com/fatima-meers-artwork-a-miraculous-testament-against-forgetting/.

Constitutional Hill. 2025. The Old Fort. Accessed 05 16, 2025. https://www.constitutionhill.org.za/sites/site-old-fort.

Davie, Lucille. 2020. Looking back on the restoration of the Johannesburg's Old Fort. April 14. Accessed May 16, 2025. https://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/looking-back-restoration-johannesburgs-old-fort.

Ennis, Clair. 2020. "SA History." Women's Jail old fort and its impact. 20 5. Accessed 03 16, 2025. https://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/womens-jail-old-fort-and-its-impact-claire-ennis.

Feakins, Charlotte, Emma Barrett, and Marlee Bower. 2024. "Trauma-heritage: towards a trauma-informed understanding of heritage." International Journal of Heritage Studies 30 (8): 857-871. Accessed May 17, 2025. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2024.2342286.

Fereshteh, Kovacs. 2015. "From Traumascape to Trauma-escape (Memory versus Oblivion)." Research Gate. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Fereshteh-Kovacs/publication/323542498_From_Traumascape_to_Trauma-escape_Memory_versus_Oblivion/links/5a9b15190f7e9be37966258b/From-Traumascape-to-Trauma-escape-Memory-versus-Oblivion.pdf.

Hartmann, Rudi, John Lennon, Daniel P Reynolds, Alan Rice, Adam T Rosenbaum, and Philip R Stone . 2018. "The history of dark tourism." Journal of Tourism History 10 (3): 269-296.

ICOMOS. 2017. GUIDANCE ON POST-TRAUMA RECOVERY AND RECONSTRUCTION. Paris: ICOMOS.

Jones, Siân. 2017. "Wrestling with the Social Value of heritage: Problems, Dilemmas and opportunities." journal of community archaeology & heritage 21–37.

Madikida, Churchill, Lauren Segal, and Clive van den Berg. 2008. "The Reconstruction of Memory at the Constitutional Hill." The Public Historian 30 (1): 17-25.

Maria, Tumarkin. 2019. "Twenty Years of Thinking about Traumascapes." Fabrications (Routledge) 29 (1): 4-20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10331867.2018.1540077.

Mogoboya, Motlatjo. 2022. History, art and remembering: women's experiences of incarceration at Constitution Hill Women's Prison. 9 7. Accessed 03 16, 2025. https://www.up.ac.za/faculty-of-humanities/news/post_3093790-history-art-and-remembering-womens-experiences-of-incarceration-at-constitution-hill-womens-prison.

Ndoro, Webber. 2018. "Drawing parallels: authenticity in the African context - until lions learn to write, hunters will tell their history then." Revisiting authenticity in the Asian context. Sri Lanka: Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), Republic of Korea. 37-47.

NHRA. 1999. "National Heritage Resources Act 1999." Government Gazette 19974. Cape Town: Republic of South Africa, April 28.

Noort, Elvira van. 2005. Mail & Guardian. 29 7. Accessed 03 16, 2025. https://mg.co.za/article/2005-08-29-vivid-memories-of-a-dark-heritage/.

SAMHSA. 2014. SAMHSA's Concept and Guidance for Trauma-Informed Approach. Department of Health & Human Services (USA), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville: HHS Publications, 27. Accessed May 17, 2025. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources/resource-guide/samhsa_trauma.pdf.

Sharon, Macdonald. 2009. DIFFICULT HERITAGE Negotiating the Nazi past in Nuremberg and beyond. Oxon: Routledge.

STOVEL, HERB. 2008. "Origins and influence of the Nara document." APT Bulletin 9-17.

Tunbridge, J E, and G J Ashworth . 1996. Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the past as a resource in conflict. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.