Ngwao no 2: Negotiating Heritage and Development - A reflection on choosing both.

To say that heritage is against development is, in fact, not the truth. When you examine the definition of heritage, it is not stagnant; it is an active concept. Similarly, development is a continuous and ongoing process. What is clear is that these two words tend to be in tension with each other. Those dealing with heritage often find themselves having to choose between heritage and development. However, during the block week, I learned that it is not about choosing one of them, but about how to choose both. In this essay, I will discuss how heritage and development can coexist. To unpack the complex relationship between heritage and development, I draw on our group reading, "Rethinking Heritage for Sustainable Development" by Sophia Labadi. My argument is that the perceived binary between heritage conservation and urban development is false and unproductive. Instead, heritage is a living, evolving framework that must be integrated into development decisions. This essay is structured around the thematic days of the block week to demonstrate how heritage, when approached dynamically and ethically, supports rather than hinders transformation.

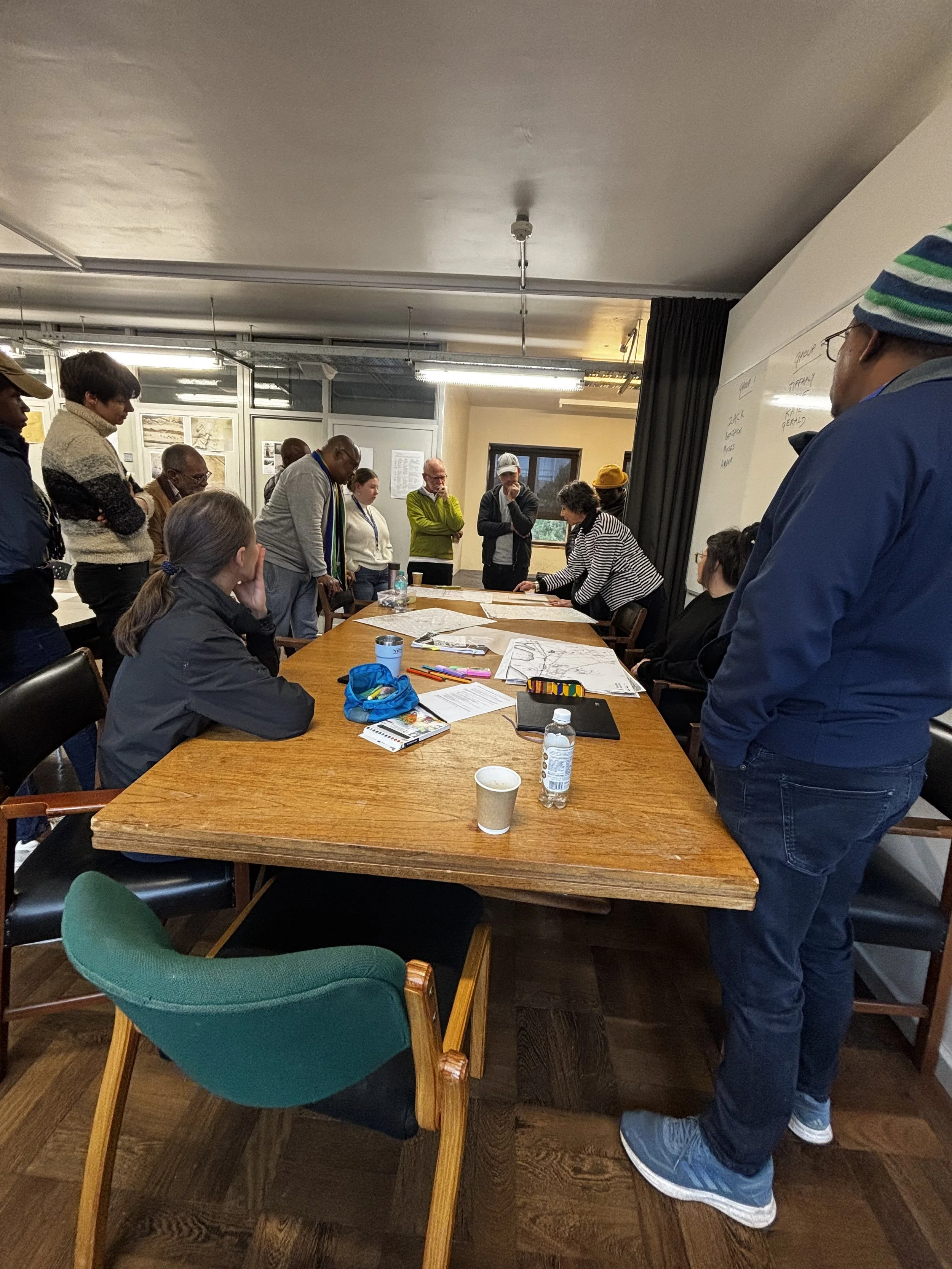

Class discussing the challenges of development and heritge within Salt River with Onwar Omar. Photograph by author, 2025.

During our reading discussion, a paper that stood out to me was Sophia Labadi's text, which discusses the role of heritage in sustainable development, particularly in the context of sub-Saharan Africa, highlighting its potential contribution and the challenges faced in integrating heritage into broader development agendas. I was excited by her work, as I believe that due to our rich, complex, and lived heritage in South Africa, we have no choice but to develop with heritage in mind. We need a paradigm shift in how heritage is perceived and managed to ensure it effectively supports poverty reduction, gender equality, and environmental sustainability. My appreciation of the role that heritage plays in development in South African town and urban scapes deepened because development is a need that prioritises local needs, voices, and participation.

On the second day, it was evident that our complex and violent spatial injustices are ever-present in our day-to-day lives. This layer cannot be ignored, as it manifests itself in the physical built forms we find in our towns and urban landscapes. Through discussions following the presentations, it became evident that we need to work through the messiness to truly understand systemic discrimination, stereotypes, and ingrained power dynamics in order to address structural inequalities. I have come to appreciate that we cannot have a one-size-fits-all approach to heritage and development in the country, as these injustices exist differently in different parts of the country.

The experience of mapping and visiting Salt River made tangible the tensions between heritage, gentrification and inclusive planning. Our current urban realities have made cities and spaces that were once demarcated for certain racial groups melting pots of culture. This is a result of economic conditions that developers leverage. Whose heritage? It was clear from the proposed housing developments that developers often dismiss local narratives for economic gain. Labadi warns against international frameworks that impose foreign ideals onto local communities, arguing instead for co-created approaches grounded in local dignity1. The value of this experience lies in the fact that the contestation surrounding factory buildings, housing, and communal memories highlights the need for community consultation and the incorporation of living heritage values into planning decisions.

Briar Road, Salt River Street elevation showing how development and heritage is being “weighed up”. Photograph by author, 2025

Building on our site visit, we discussed the law, rights, and the role of institutions. Our discussions clarified how legal frameworks, such as the NHRA, SPLUMA, and municipal by-laws, can support or undermine inclusive heritage development. Building on the work from the previous week, it was clear that we needed to balance the competing interests of the state, civil society, and the private sector. Labadi's emphasis on social justice, epistemological pluralism, and power-sensitive policy echoes the tensions we observed2. I left with a sharper understanding of the risks of applying blanket heritage frameworks, which erase complexity. In the peri-urban and rural contexts where I work, this means understanding how indigenous customs evolve in response to new spatial conditions and how planning should support, rather than hinder, their transformation.

The week confirmed that heritage and development are not opposing forces. They are interdependent, always in negotiation. The week's discussions and texts clarified that the question is never 'either heritage or development, but always how both coexist meaningfully in a country that needs both. This co-existence demands reflexivity, ethics, and constant engagement with people who live heritage daily.

The Archive Apartment Block is an example on how a development can interpret the architectural language of the neighbourhood to make it fit within its context and still develop. Photograph by author, 2025.